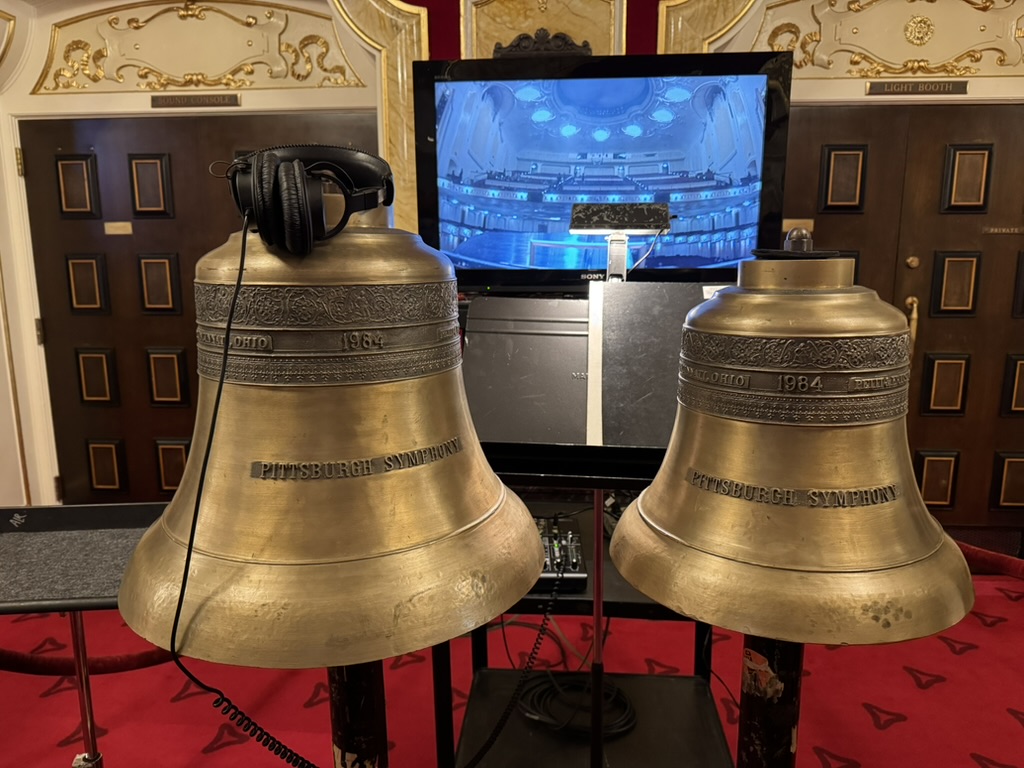

Members of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and Carnegie Mellon School of Music

Carnegie Music Hall

Pittsburgh, PA

November 24, 2025

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-flat major, BWV 1051

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049

Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos have nothing to do with the holidays, yet their cheery, celebratory spirit makes them a favorite this time year. A survey of the complete series made for a satisfying evening at Chamber Music Pittsburgh during the week of Thanksgiving. No two of these concertos are scored for the same instrumentation, and a wide panoply of performers were culled from the ranks of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and the Carnegie Mellon School of Music.

No conductor was engaged (and nod to historical practice), and modern orchestral instruments were used (a nod to contemporary practice). And instead of proceeding in strictly numerical order, thoughtful contrasts and complements were suggested. The evening began with No. 3, a slighter work cast for strings alone, but charming and radiant nonetheless.

In No. 1, the strings were in mellifluous blend with the winds and brass (although the intonation of the horns left something to be desired). Under the astute leadership of violinist Callum Smart, the ensemble was in tight cohesion, culminating in the regal rhythms of the closing polonaise. Concerto No. 2 was marked by the resound of the clarion trumpet, in an impossibly high register.

No. 5 is a pianist’s dream with its outsized role for the keyboard. The remarkable Frederic Chiu was featured as soloist, playing on a modern Steinway rather than a harpsichord or fortepiano. He had a sparkling chemistry with the ensemble, with self-assured playing that rippled across the keyboard, and offered a mesmerizing take on the massive cadenza. No. 6 is perhaps the most intimate and understated of them all, and I liked the rich, husky tone the musicians conveyed. With a pair of flutes (used in place of recorders) and a complement of strings, the gentle and pastoral No. 4 drew the set to a spirited, heartfelt close.