Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Jakub Hrůša, conductor

Symphony Center

Chicago, IL

May 18, 2017

Smetana: Má vlast

While Smetana’s Vltava (more commonly branded in its German rendering of The Moldau) is a well-known quantity, the cycle of six tone poems from where it comes, collectively titled Má vlast, has become something of a rarity outside the composer’s Czech homeland. So much so that Thursday night’s performance was the CSO’s first traversal of the complete work in over three decades – the score was last visited by the Czech former music director Rafael Kubelík in 1983, and later by James Levine on a 1987 Ravinia program.

Smetana’s magnum opus served as a fine platform for the talented young conductor Jakub Hrůša – recently named principal guest conductor of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra – to make his CSO debut, and by all accounts, it was a success. The last time I caught a performance of the complete Má vlast was at the Pittsburgh Symphony under Jiří Bělohlávek, with whom Hrůša studied – in each case, I was struck how both conductors managed to commit the expansive score to memory, a testament to the importance of this work to Czech musicians.

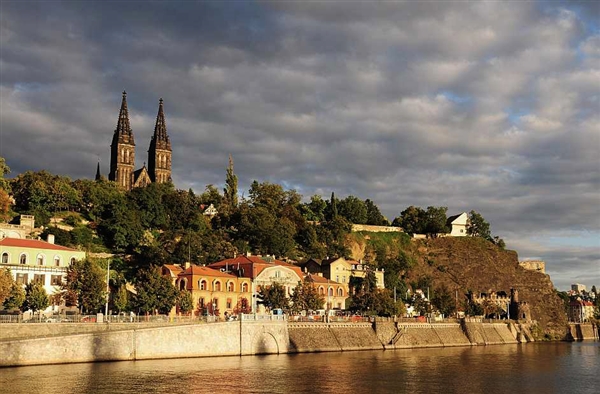

Vyšehrad, the spacious opening selection, invoked the titular ancient fortress in Prague with a stentorian theme in the brass that recurred throughout the cycle. It began with the two harps in a rhapsodic passage, given freely without Hrůša’s conducting, as if a minstrel telling a tale. The piece built to powerful brassy climaxes, but the terraced dynamics were controlled in such a way that matters never fell into empty bombast, and a quiet, contemplative statement of the Vyšehrad theme closed this first tone poem.

Vltava had particular poignancy in assuming its rightful place in the context of the cycle. A pair of liquescent flutes depicted the two streams that converge to form the mighty river, and the river’s journey was traced in vivid detail. The famous primary theme was given with a sweeping passion, while in due course there was portrayal of the bubbling St. John’s Rapids, a spirited peasant wedding, and most memorably, the mystical atmosphere of the water nymphs. Signaling the river’s arrival in Prague was fittingly a further invocation of the Vyšehrad motif.

A violent intensity characterized Šárka in its garish detailing of a most gruesome tale: a battle of the sexes, wherein the titular figured commanded a battalion of warrior maidens to drug and eventually murder a group of unsuspecting men. Šárka herself was represented via a sinuous clarinet line, very finely played by Steven Williamson, and the work grew to wild, unrelenting heights, with the trombones adding a shattering heft to the coda.

Z českých luhů a hájů (translated in the program books as From Bohemia’s Field and Groves) is certainly a highpoint of the set. Despite its innocuous title, it began with a turbulent pathos, giving way to a sophisticated and expertly articulated fugato, perhaps suggesting the complexity of the Czech people who embody more than mere rustic simplicity. Still, the tone poem positively exuded a joie de vivre in a theme initiated by the mellifluous horns.

The final two works were written as an afterthought to the preceding, yet they are inextricably linked both to each other and to the cycle as a whole. Tábor opened with a defiant statement of a Hussite chorale, perhaps mirroring the defiance with which Smetana feverishly composed music in the face of deafness. A sweet choir of winds added some contrast, while the propulsive intensity of the main theme was grinded out by the low strings.

The concluding Blaník, named for a mountain where according to legend, St. Wenceslas’ army lay dormant but prepared to rally in a time of great need, picked up right where Tábor left off. This time, however, the chorale was noticeably brighter, a hint to the glorious direction the music was headed. Appropriately, it concluded with a final pronouncement of the venerable Vyšehrad theme, now triumphant and victorious in the shining CSO brass.