Pablo Ferrández, cello*†

David McCarroll, violin†

Justine Campagna, violin*

Dylan Naroff, violin†

Zhenwei Shi, viola*†

Anne Martindale Williams, cello*†

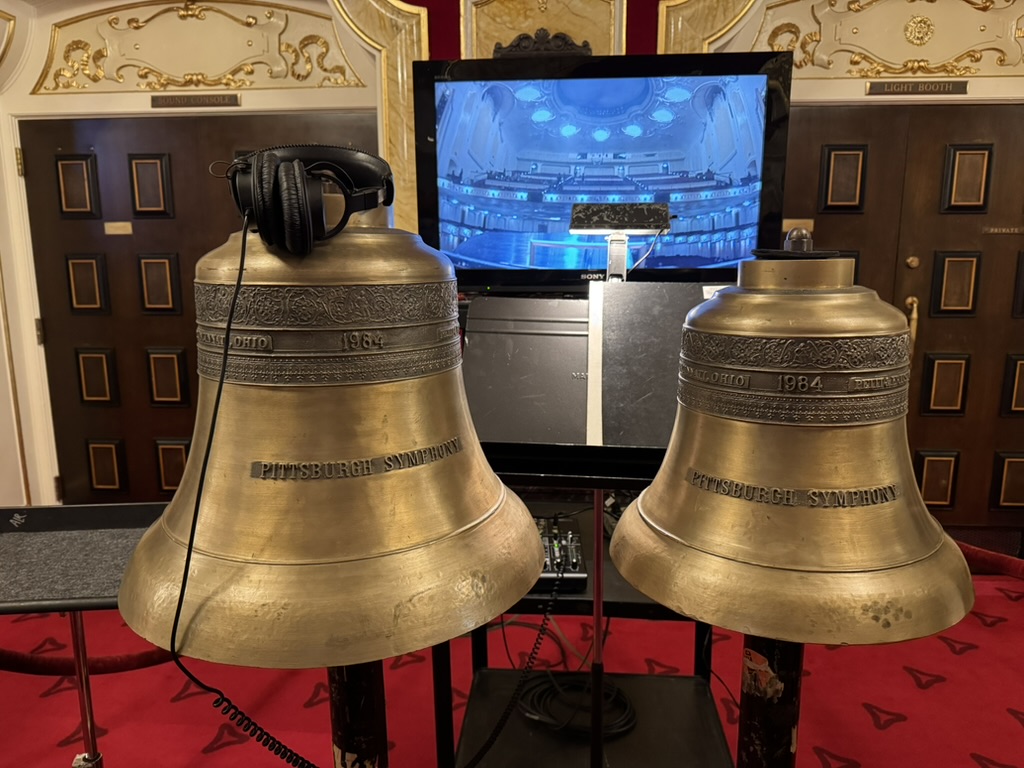

Heinz Hall

Pittsburgh, PA

November 15, 2025

Arensky: String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Op. 35*

Schubert: String Quintet in C major, D956†

Following his lyrical and refined performance of Saint-Saëns with the Pittsburgh Symphony, the next evening cellist Pablo Ferrández was featured in a PSO360 program alongside string players drawn from the orchestra’s ranks — the first three of the violins, principal viola, and principal cello. Both the works programmed were strikingly scored for two cellos: the first a remarkable discovery, the latter, a pillar of the chamber repertoire.

Anton Arensky’s Second String Quartet quite unusually doubles the cellos in place of the violins. I know of no other works with this scoring, but the rich sound makes it an instrumentation with intriguing potential. A resonant Russian hymn opened, a theme that would return at key hingepoints. Energetic, expressive, and virtuosic, Ferrández and the PSO players offered a well-balanced reading with taut communication.

The central movement was cast as a set of variations on a theme by Tchaikovsky (namely, the fifth of the Op. 54 Children’s Songs), a lovely homage from one composer to another. Arensky would go on to expand this movement as a standalone piece for string orchestra (catalogued as Op. 35a). I particularly enjoyed the fourth variation with its remarkably textured oscillations between pizzicato and arco playing, and the sleight-of-hand sixth variation was sprightly and buoyant. The finale made use of the Russian coronation anthem Slava!, and the intricate counterpoint of a fugato section made for a breathless close.

Schubert’s great C major string quintet is certainly the pinnacle of the form, and made for a rewarding second half. The spacious first movement was paced with ample room to breathe, and an intensely lyrical theme enveloped one in the richness of the two cellos (I loved the musical chemistry between Ferrández and Anne Martindale Williams). A profound lyricism was achieved in the slow movement, countered by the energy and rustic abandon of the scherzo — the trio of which had some strikingly spellbinding harmonies. The finale was given with an infectious rhythmic snap, in no way glossing over its delicate details.

In a way, this continued what’s been of brief exploration of Schubert’s late chamber music, following a recent post-concert performance of a movement from the D887 quartet. The originally announced program was to include a string quintet transcription of Beethoven’s Kreutzer sonata in place of the Arensky — a work which I’m nonetheless keen to explore.