Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

Robin Ticciati, conductor

Francesco Piemontesi, piano

Heinz Hall

Pittsburgh, PA

October 10, 2025

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58

Encore:

Mozart: Piano Sonata No. 12 in F major, K332 – 2. Adagio

Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14

The second week of the Pittsburgh Symphony’s 2025-26 subscription season saw the first of several debuts on tap in British conductor Robin Ticciati. The program was comprised of two major and deeply rewarding works, one at the precipice of Romanticism, the other, the epitome of Romanticism. Beethoven’s genial Piano Concerto No. 4 brought back pianist Francesco Piemontesi, last appearing on this stage just a few months ago.

The solo piano opened the work with a gentle resonance, followed by a long-breathed orchestral exposition. The most intimate and personal of Beethoven’s five piano concertos, Piemontesi drew deep reserves of expression. His thoughtful, probing playing perhaps recalled that of his mentor, Alfred Brendel, and he found great drama in the cadenza. In the Andante con moto, coarse strings introduced the plaintive piano, arriving at a spiritual stasis amidst moments of agitation. As if unsure what direction to go after, the closing rondo started in hesitation before robustly bursting forth with vigor and abandon. For an encore, the pianist selected a lovely slow movement from a Mozart sonata.

Revolutionary a work as it may be, Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique was written only three years after Beethoven’s death. Tentative beginnings introduced a dreamlike trance, and Ticciati teased out the richness of the strings, favoring minimal vibrato. I was struck by his energetic conducting, nearly using his entire body as his baton danced along to the music. Still, at times the orchestral balance left something to be desired. The first presentation of the idée fixe that binds the work was graceful and filled with longing.

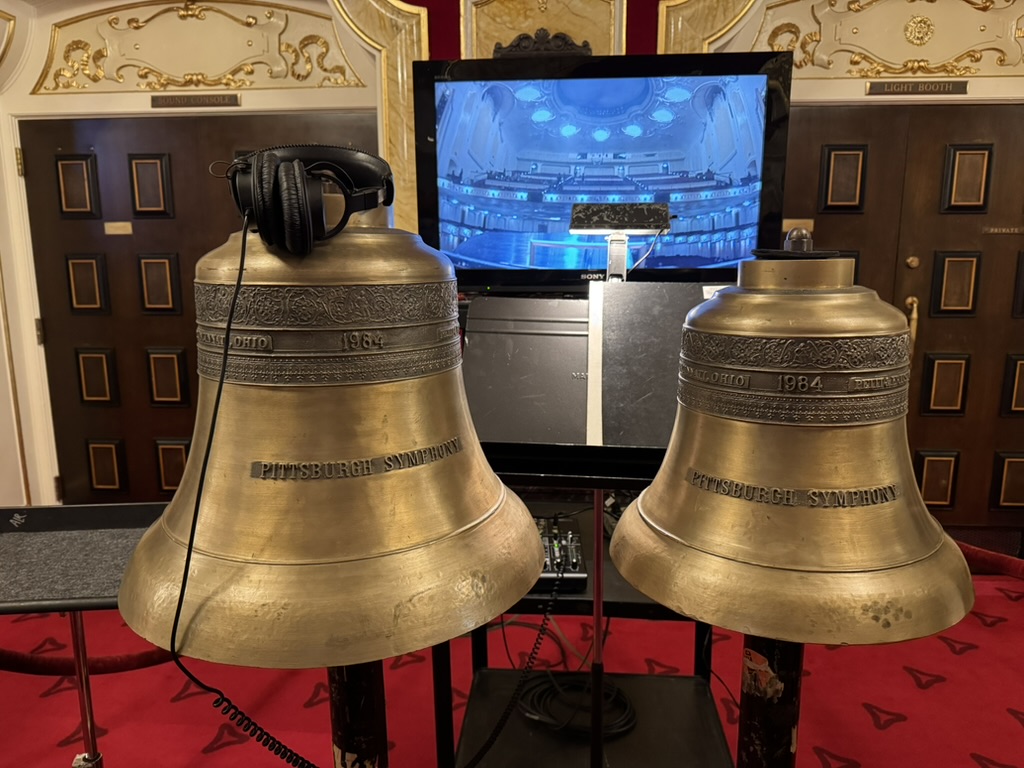

In Un bal, the harps introduced an elegant waltz theme; a striking dialogue between English horn and offstage oboe opened the central Scène aux champs. A widely contrasting portrait of nature, matters went from the calm to the passionate to the stormy, ending with the forlorn English horn all alone. Matters came alive in the iconic Marche au supplice, given an energetic workout in all its brassy splendor. The closing Songe d’une nuit du sabbat opened in an eerie soundscape, filled with the striking timbres of the shrill E-flat clarinet, tolling bells (performed offstage from the lobby), and a chilling invocation of the Dies irae chant in the low brass.

In a post-concert performance, Piemontesi teamed up with PSO wind players for the latter two movements of Beethoven’s Quintet for Piano and Winds. A lovely pendant to the evening, and given the pianist’s chemistry with these players, I’d love to see him perform as part of the orchestra’s PSO360 series.

Two personal notes. One of my fondest concert memories consists of this same Beethoven/Berlioz pairing. The first of many performances I attended at Vienna’s Musikverein during a formative college year in the Austrian capital, conductor and piano were respectively Claudio Abbado and Maurizio Pollini — two of my musical heroes who are sadly no longer with us.

I am eagerly anticipating Marc-André Hamelin’s next album Found Objects/Sound Objects, due for release at the end of the month. In quintessential MAH fashion, it’s an enterprising blend of little-known works mostly dating from the last half-century. The disc concludes with his own Hexensabbat (Witches’ Sabbath). With obvious allusions to the Berlioz (including use of the Dies irae), how fitting it was for the track to be released as a single the same day as the PSO performance — and it’s a thrilling listen.