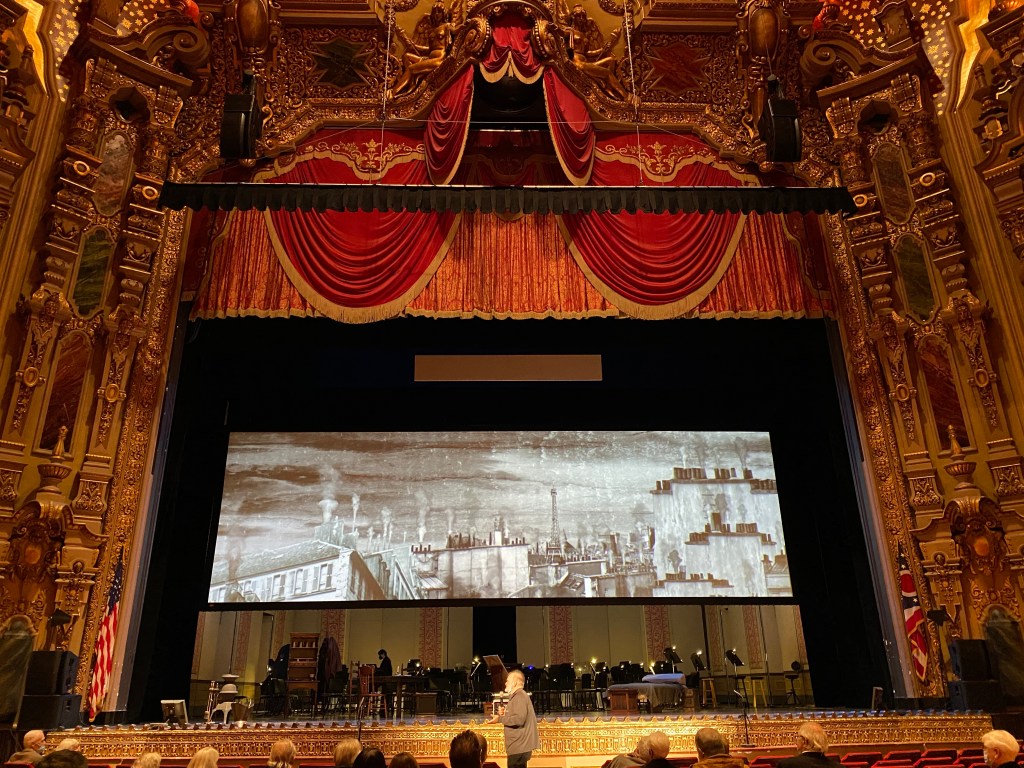

Rossen Milanov, conductor

Columbus Symphony Orchestra

Ohio Theatre

Columbus, OH

January 20, 2023

Beethoven: Leonore Overture, Op. 72b

Mozart: Symphony No. 36 in C major, K425, Linz

Haydn: Symphony No. 100 in G major, Hob. I:100, Military

Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven are all but synonymous with the classical style, and this weekend’s Columbus Symphony program offered one sterling example from each of these Viennese masters (and although indelibly associated with the Austrian capital, none were in fact natives). Beethoven produced no less than four overtures for his sole opera Fidelio; the third, bearing the opera’s original title Leonore, opened the program. Ripe with operatic drama, it functions well as a standalone concert piece – and in the opera house, it has become a long-standing tradition to inject this version between scenes in the second act.

Somber beginnings gave rise to dramatic tension, thoughtfully paced by Milanov. Offstage trumpets sounded as a fanfare, suggesting narrative details of the source material, and the work ended in brassy splendor. Slow introductions were par for the course in Haydn’s symphonies, but rather rare for Mozart’s output. He employed such a device for the first time in the Linz symphony (No. 36), a technique he would only revisit twice (nos. 38 and 39). It made for a stately opening, setting up the effervescent main subject of the movement proper, given with airy clarity.

The Andante made for a gentle interlude, though punctuated by insistent brass and timpani. A most elegant of minuets followed, with Milanov’s baton bringing emphasis to the sprightly triple meter. The finale was lithe, lean, and joyous – one of Mozart’s most untroubled creations.

The introduction to Haydn’s Military symphony was given with clarity and careful articulation; the main theme was established with the unusual scoring for flute and oboe, and matters proceeded with a refined charm. Over two centuries later, the Allegretto which gives this symphony its moniker is still so striking and wonderfully surprising with its ceremonial percussion and brass fanfare. Such a movement is a hard act to follow, but the minuet was full of wit and charisma, with playing from the well-rehearsed CSO boasting the requisite transparency demanded by this repertoire. A vigorous return of the percussion made the finale an especially exciting affair.