Columbus Symphony Orchestra

Rossen Milanov, conductor

Natasha Paremski, piano

Ohio Theatre

Columbus, OH

May 3, 2024

Lutosławski: Symphony No. 1

Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

Clyne: This Moment

Strauss: Suite from Der Rosenkavalier, Op. 59

Last weekend’s Columbus Symphony program was of particularly inspired and enterprising programming, traversing three works from various points of the 20th-century, and a fourth work composed just last year. Witold Lutosławski was at the vanguard of midcentury modernism, and like Shostakovich and Prokofiev, saw his works heavily repressed by the communist authorities. Such was certainly the case for his First Symphony, composed 1941-47 – during and in the immediate aftermath of WWII – which was suppressed for a decade after its first performance.

It’s a landmark work, to be sure, brimming with the composer’s individual voice but readily accessible, and kudos to Milanov for giving the first Columbus hearing. In his spoken introduction, the conductor reminisced about meeting Lutosławski while a student in Pittsburgh. Cataclysmic beginnings were to be had in the work, uncompromisingly expressing the bleak spirit of the times – much to the chagrin of the Soviet apparatchiks. The brass provided a certain sheen of brightness, and piano and harp further added to the colorful scoring.

An extended slow movement saw low strings underpinning a horn solo, giving some semblance of peace after the cacophony of the preceding, but not without a certain unease with its pained lyricism. A flowing solo passage from concertmaster Joanna Frankel ranged from the subdued to the impassioned. The Allegretto misterioso was eerie and mysterious, and its fleeting quality reminded me of the Schattenhaft from Mahler’s Seventh. A shimmering interlude near the movement’s close was quite striking before the finale returned to the vigor of the opening. Hats off to the CSO for a blistering performance of a complex score.

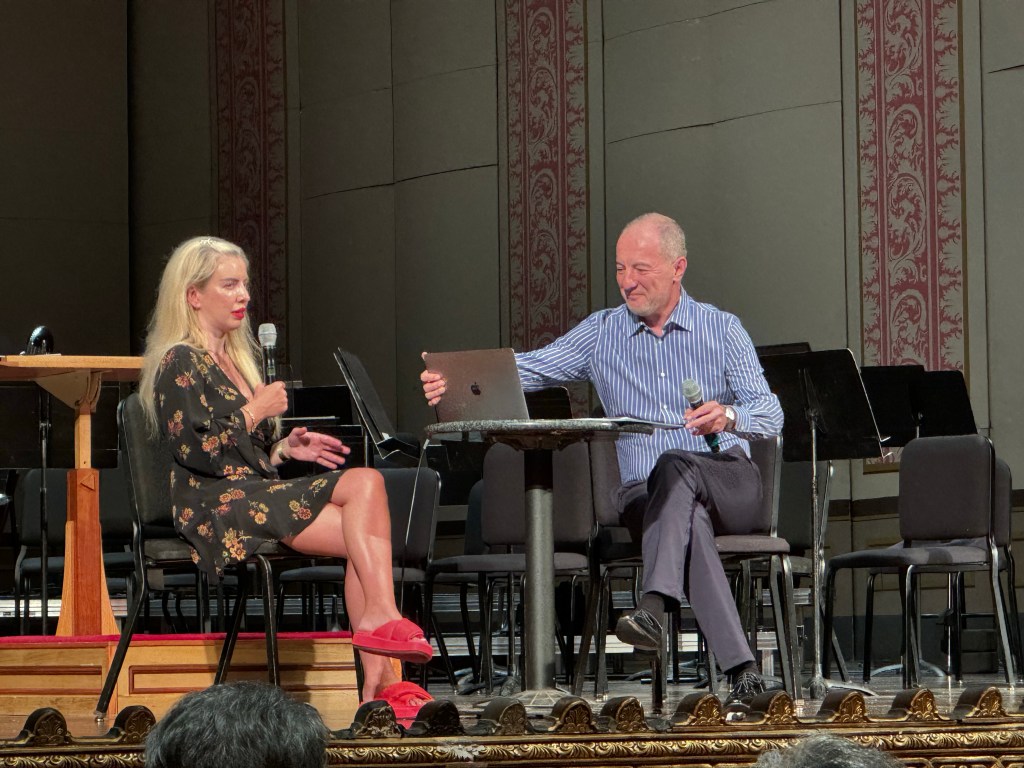

Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini was certainly more familiar territory, and brought forth Natasha Paremski as soloist. Paremski was further on hand for a preconcert interview with Milanov (as a sidebar: could Milanov please let his guests speak uninterrupted?). Matters began with a thundering articulation of the skeleton of the ubiquitous theme, and Paremski took things at a rapid, unsentimental tempo, supported by her impressive fingerwork. Variation 7 introduced the Dies irae theme in a meditative manner before building to crashing double octaves. Variation 18 was suitably sumptuous while skirting the saccharine, and Paremski had no shortage of pianistic fireworks in the final variations before the flippant closing gesture.

Anna Clyne’s This Moment came about on commission from the League of American Orchestras, as part of an initiative to proliferate music by women composers. The title alludes to a quote from Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh: “this moment is full of wonders.” The work further invokes quotes from the Kyrie and Lacrimosa of Mozart’s Requiem, which Milanov helpfully had orchestra members demonstrate (and in the present context, perhaps also offered a thematic connection to the Dies irae from the Rachmaninoff). Meditative stillness seemingly stretched the moment, building to more strident material. It’s an appealing piece, but ultimately its six-minute duration didn’t make the strongest impression as a standalone work.

A suite from Strauss’ opera Der Rosenkavalier closed the evening. From bar one, the Ohio Theatre was enveloped in its lush, honeyed, excess. I was struck by the richness of the strings, as well as fine playing from the winds with a standout oboe solo. The Ochs-Waltzes were elegant, stylish, and echt-Viennese, and the suite crested to searing passion.