Cleveland Orchestra

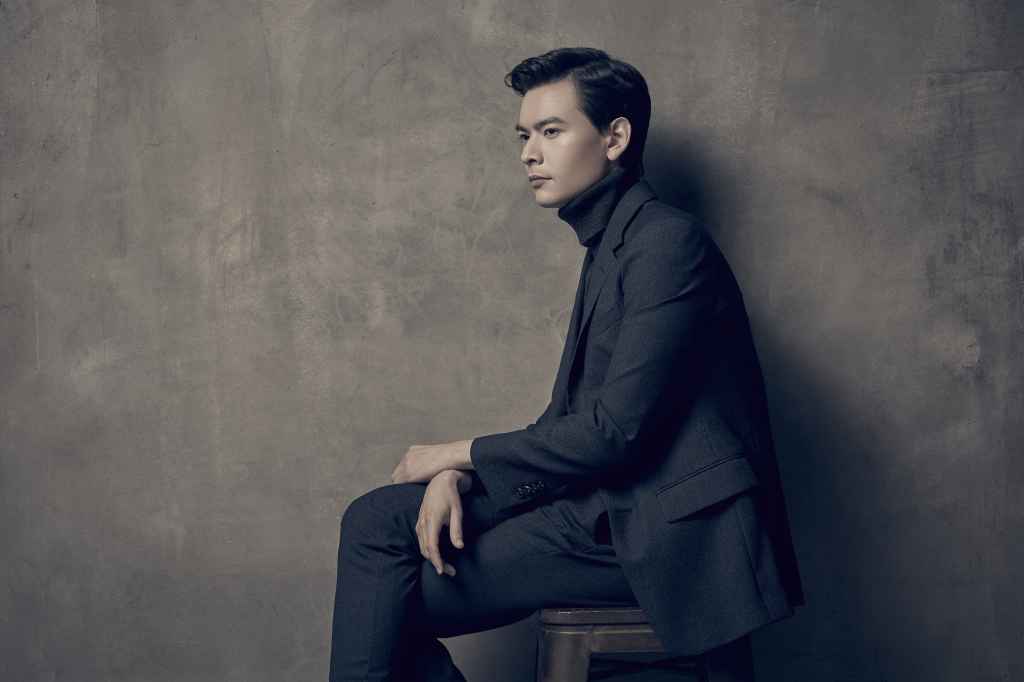

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Mandel Concert Hall

Severance Music Center

Cleveland, OH

January 15, 2022

Mozart: Symphony No. 36 in C major, K425, Linz

Deutsch: Intensity

Dvořák: Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88

Under the baton of music director Franz Welser-Möst, The Cleveland Orchestra offered familiar and appealing symphonies of Mozart and Dvořák as bookends to a compelling premiere from its current composer in residence. Mozart’s Linz symphony made for a pearly opener. The dotted rhythms which opened the slow introduction were punctuated with heft while the ensuing Allegro spiritoso was a fittingly lighter affair, given with such energy as to mirror the frenetic pace at which it was composed. The Andante was delicate and intricately refined by way of Welser-Möst’s exacting attention to articulation and dynamics. In the Menuetto, one was struck by the rhythmic swagger, and the bold, big sound of the modern orchestra which the conductor cultivated – something of a foil to Nicholas McGegan’s airier and comparatively more historically-informed performance of the work a few seasons ago. Contrast was further sharpened by the rather more genial trio, and the finale was given with crystalline clarity even at breakneck tempo.

Bernd Richard Deutsch’s Okeanos made a strong impression on this listener when performed by the orchestra in March 2019 (and captured on the excellent A New Century). As the current Daniel R. Lewis Young Composer Fellow, Deutsch was commissioned to write a new work for TCO, originally slated for a May 2020 performance but inevitably postponed until this weekend. The product of this residency was Intensity, an aptly titled twenty-minute fantasy scored for massive orchestral forces – including a particularly extensive percussion battery. A sense of wound-up energy, pregnant with potential permeated the opening bars, and the colorful timbres of the percussion were utilized from the opening notes. Lyrical interludes at various interludes offered an anchor in otherwise stormy waters. The middle of the work’s three sections was spectral and dissipated, achieved through the striking aural palette of high strings, muted brass, percussion, and celesta. The namesake intensity ramped up again in the final section, encouraged by the boisterous percussion and finally culminating in a blast in the brass. A fitting tribute to the virtuosity and technical prowess of the The Cleveland Orchestra, and I hope a recording is released in the near future.

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8 is certainly one of the most popular in the repertoire, but this performance was refreshingly far above the routine and pedestrian. Passionate beginnings, as coaxed from the resonant cellos, persisted for only a moment before the work’s sunny disposition shone through. Joshua Smith’s solo flute passages were a highlight, and Welser-Möst opted for a brisk tempo, keenly avoiding over-sentimentalizing. The Adagio showed Dvořák at his most lyrical, although a brilliant brass section added bold contrast. The Allegretto grazioso positively sparkled in its lilting textures, while clarion trumpets heralded the finale wherein the conductor guided the orchestra with conviction through the myriad of guises of this rousing theme and variations.