Columbus Symphony Orchestra

William Eddins, conductor and piano

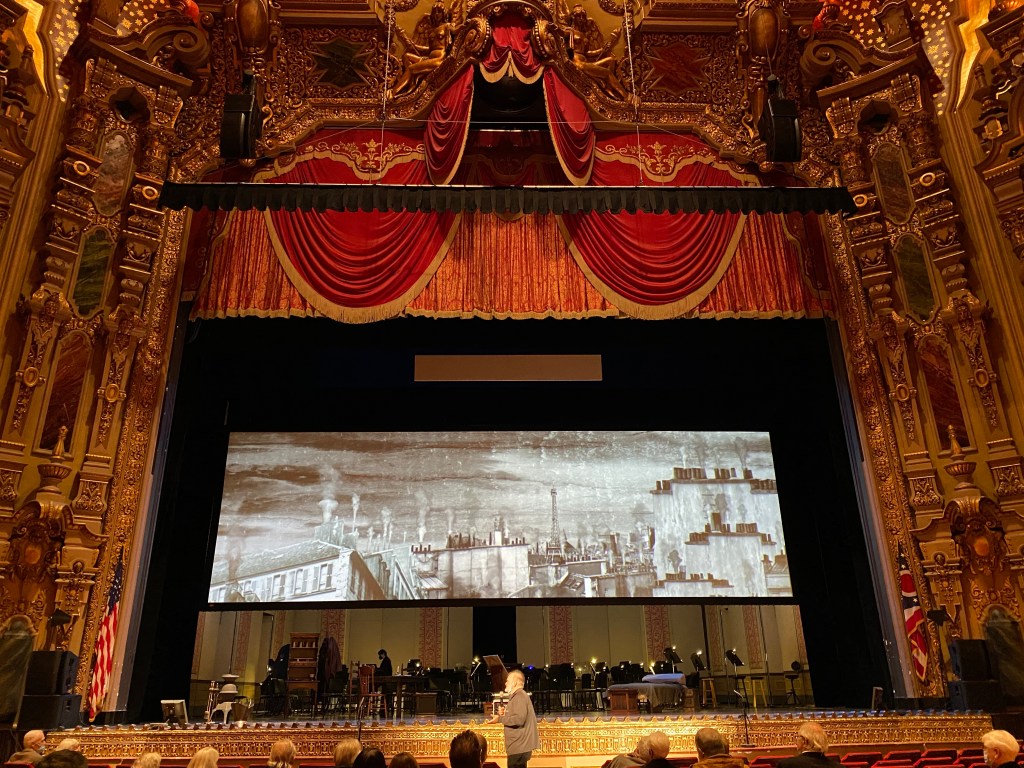

Ohio Theatre

Columbus, OH

February 20, 2022

Perkinson: Sinfonietta No. 1

Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue (1926 orchestration, Grofé)

Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

Guest conductor Williams Eddins led the Columbus Symphony last weekend in a decidedly populist program, though matters nonetheless opened with an unfamiliar work by an unfamiliar composer. The quantity in question was the Sinfonietta No. 1 by African-American composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, named after Samuel Coleridge-Taylor who perhaps served as a guiding inspiration to the younger composer. A compact three-movement work dating from 1954, the work opened with angular gestures though generally lyrical at heart, colored by piquant harmonies. A mournful slow movement seemed to echo Barber’s Adagio for Strings (this work too was scored for strings alone), while the vigorous finale purveyed textures akin to a Baroque concerto grosso. A finely crafted product of midcentury America given with compelling advocacy from Eddins and the Columbus strings.

Eddins served double duty as pianist and conductor in Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, but first took several minutes to introduce the work – as historically-informed as it was entertaining. Principal clarinet David Thomas delivered the iconic opening in a sultry solo. The work was presented in its 1926 pit orchestra scoring for an authentic feel of the roaring twenties, and it was certainly fitting for the performance to take place in a venue that was a product of the same decade. Eddins proved equally adept at both roles, and guided the ensemble in a charismatic, high-octane performance.

It’s a challenge for conductors to make such a well-worn piece as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony sound fresh. I wasn’t convinced Eddins managed to say anything novel, but the performance nonetheless served as an always welcome encounter with an old friend. The opening Allegro con brio benefitted from Eddins’ energetic conducting, an intensity countered by the warm lyricism of the strings in the slow movement – though I found the brass to be a bit overzealous. The scherzo started out as a whisper, employing the ubiquitous rhythmic gesture that binds the work, and gradually grew in urgency. Matters were held in suspense until the brassy C major finale broke through the clouds. Still, the journey is far from over – Beethoven has gift for profligate finales! – and the energy on stage seemed to flag for a somewhat anticlimactic ending.