Columbus Symphony Orchestra

Rossen Milanov, conductor

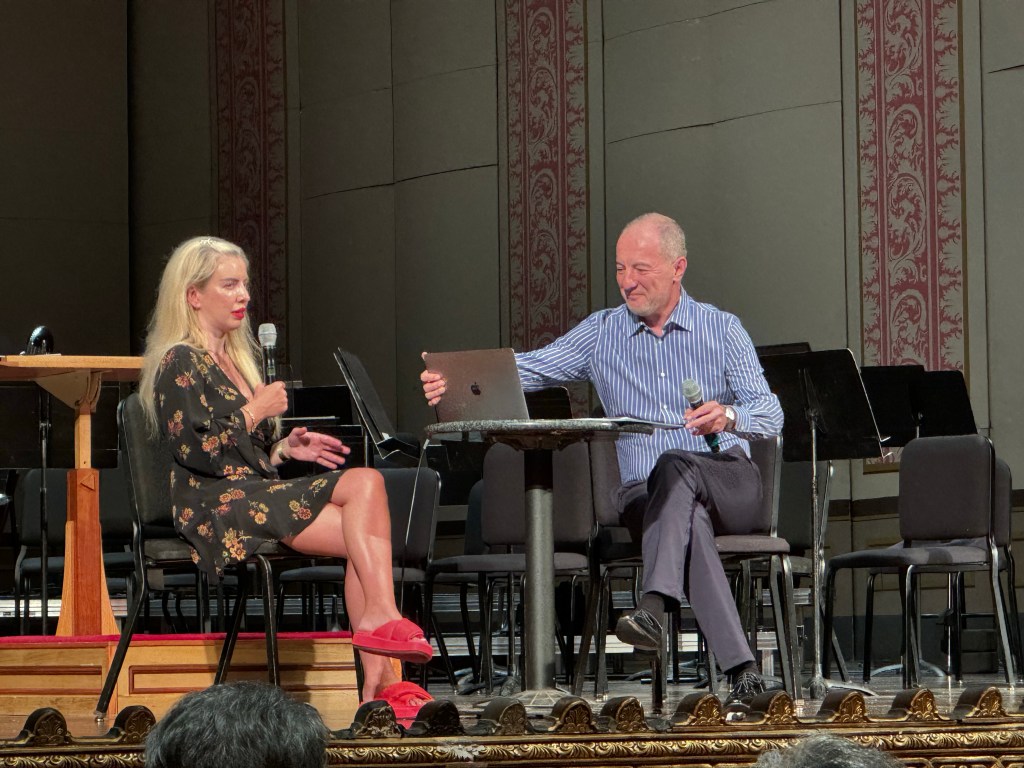

Aubry Ballarò, soprano

Hilary Ginther, mezzo-soprano

David Walton, tenor

James Eder, bass

Stephen Caracciolo, chorus director

Columbus Symphony Chorus

Ohio Theatre

Columbus, OH

May 24, 2024

Mozart: Mass in C minor, K427, Great (completion by Ulrich Leisinger)

For the final program of the 2023-24 Masterworks season, the Columbus Symphony offered a single work in a brief but affecting program, an evening dedicated to Mozart’s C minor mass. Like the Requiem, Mozart never completed the Mass, and the CSO presented the work in a 2019 realization by Ulrich Leisinger, which eschews a liturgically complete mass in favor of only minimal additions to Mozart’s extant corpus.

Under Rossen Milanov’s baton, the opening Kyrie began intimate and inward, quite striking for such a grandiose conception. Matters quickly grew in urgency, however, with the Chorus – prepared by Stephen Caracciolo – filling the cavernous Ohio Theatre. “Christe eleison” was intoned by soprano Aubry Ballarò, with flowing, extended melismas yielding a resonant effect – and I couldn’t help being reminded of the passage’s use in Amadeus.

The extensive Gloria began resplendent and exultant, structured such that the chorus alternated with the soloists, either as individuals or in various combinations. Hilary Ginther offered a second soprano voice in “Laudamus te,” articulate, and in command of the vocal intricacies, while “Dominus Deus” saw her in harmonious blend with Ballarò. In “Qui tollis,” the chorus was rapt and pious in the minor key profundities. The women were combined with tenor David Walton in “Quoniam,” the latter a bit overshadowed, and the final passage of the Gloria was given to the chorus, resplendent in its exacting counterpoint.

In the Credo, a soprano solo (Ballarò) prefaced an orchestral interlude, notable for fine playing from the winds. This was somewhat lighter fare compared to the preceding, but still certainly no trifle. The Sanctus was brightened by the brass – with the trombones especially striking – and the closing Benedictus was given heft with the sole appearance of bass James Eder, though it was the chorus who ultimately brought the work to its resonant close.