Lyric Opera of Chicago

Civic Opera House

Chicago, IL

December 3, 2016

Berlioz: Les Troyens

Christine Goerke, Cassandra

Susan Graham, Dido

Brandon Jovanovich, Aeneas

Okka von der Damerau, Anna

Lucas Meachem, Chorebus

Christian Van Horn, Narbal

Sir Andrew Davis, conductor

Chicago Lyric Opera Orchestra

Tim Albery, director

Tobias Hoheisel, set designer

With works on the scale of La damnation de Faust and Roméo et Juliette to his credit, one would certainly expect an opera from Berlioz to be of the grandest proportions. Les Troyens certainly does not disappoint on that front, and Lyric Opera of Chicago’s first traversal of this epic – lasting nearly five hours – was a major achievement. Scored for a large cast, massive choir, sumptuous orchestra, and corps de ballet, this lavish production directed by Tim Albery and designed by Tobias Hoheisel was given a run of just five performances as it was no doubt a costly investment for Lyric.

Berlioz had something of an obsession with Virgil’s Aeneid on which the opera is based, and accordingly provided his own libretto, notable for its directness. The opera is conceived in five acts, further divided into two parts (The Taking of Troy and The Trojans at Carthage respectively). The central image on stage through the duration was of a mighty wall, crumbling and dilapidated in Troy, opulent and shining in Carthage, yet in a continuing arc it was the same wall, suggesting the cyclical rise and fall of human civilization. On that note, one was struck by the suggestion of the Trojan refugees crossing the Mediterranean in flight of their destroyed city, evocative of the plight of the Syrian refugees in today’s no less tumultuous political climate.

The latter part begins at the third act, and it was here the wall was rebuilt, brilliantly shrouded in pearly white light, allowing for a striking visual effect of shadows on the wall. Act IV was a highpoint with its tender moments in an otherwise bloody drama. The corps de ballet beautifully portrayed nymphs and satyrs, and Mingjie Lei’s dulcet tones depicted the poet Iopas, accompanied by the harp and oboe. The act built up to the soaring duet between Dido and Aeneas (“Nuit d’ivresse”), the otherworldly atmosphere further enhanced by celestial images of the stars and planets. In the last act, Susan Graham’s Dido was impassioned and heartwrenching in her final, desperate cries, and the opera ended with the word “ROMA” projected on the wall suggesting her parting vision of Carthage being destroyed by Rome.

Dido was originally to be sung by Sophie Koch who withdrew for personal reasons, and fortunately for local audiences a seasoned a Dido as Graham was on hand to take her place, and she provided a bounty of beautiful singing. Brandon Jovanovich’s Aeneas was imposing and authoritative, amply filling the dimensions of this substantial role. Also worthy of note was Christine Goerke as Cassandra, the daughter of Priam (king of Troy), appearing only in the first part to haplessly warn of city’s impending destruction. The chorus and orchestra, led by Michael Black and Sir Andrew Davis respectively, were major forces to be reckoned with, serving effectively as dramatic characters in their own right – unwieldy as the work may be, all the moving parts came together in tight control.

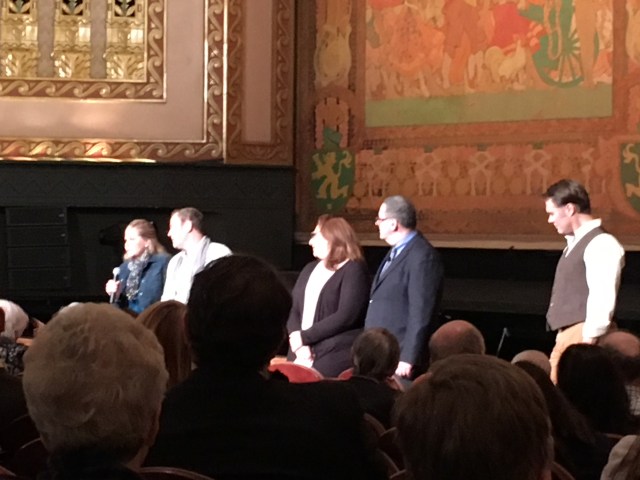

Following the curtain, there was a Q&A session moderated by general director Anthony Freud with Brandon Jovanovich, Susan Graham, Christine Goerke, and Lucas Meachem – thanks are in order to them for providing a fascinating perspective on the heels of what was surely a physically exhausting performance.