Imani Winds

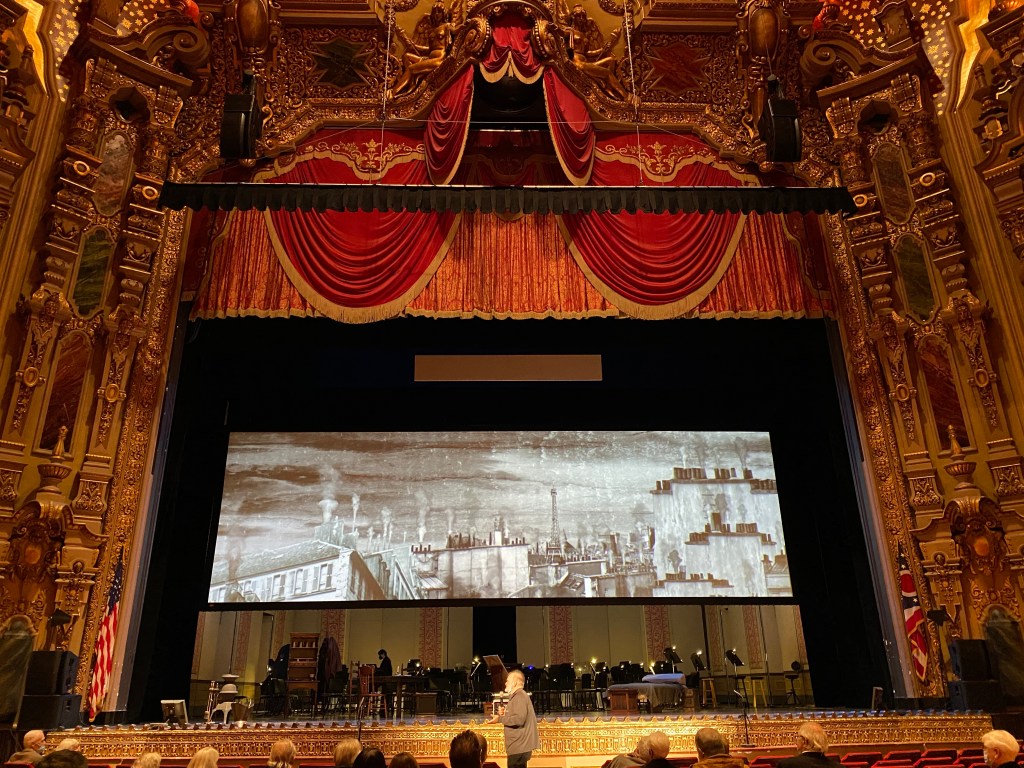

Southern Theatre

Columbus, OH

February 19, 2022

Coleman: Umoja

Nathalie Joachim: Seen

Crawford Seeger: Suite for Wind Quintet

León: De Memorias

Esmail: The Light is the Same

Coleman: Afro-Cuban Concerto

Chamber Music Columbus’ first program of 2022 brought the dynamic Imani Winds to the Southern Theatre in a diverse, wide-ranging program, with all works by women composers. Valerie Coleman’s Umoja made for a bright and joyous opening. Coleman was the founder and former flutist of Imani, and Umoja has become her signature piece; transcriptions exist for a variety of other ensembles in addition to this original incarnation for wind quintet.

Haitian-American composer Nathalie Joachim wrote Seen as part of Imani’s Legacy Commissioning Project, an initiative which has produced a wealth of new music. A recent work, premiered just last year, Seen is comprised of five short movements, one for each member of the quintet, depicting their colorful, distinctive personalities in charming vignettes. Each of their respective instruments were emphasized in turn, with the other members present but relegated to the background; in the second selection I was especially struck by the expressive range of the busy bassoon (Monica Ellis).

The first half closed with the Suite for Wind Quintet by Ruth Crawford Seeger (stepmother to folk singer Pete Seeger), a major force in twentieth century American music who likely never realized her full potential owing to the gender barriers of the time. The 1952 work employs a serialist language, sophisticated but without sounding dryly academic, and Imani handled the considerable technical challenges with grace and precision. The whirlwind finale made for an imposing close, and the taut coordination between flute (Brandon Patrick George) and bassoon was a standout.

Tania León’s De Memorias was a piquant and evocative reflection of her childhood in Cuba, contrasting a pulsating ostinato with more free-sounding, rhapsodic material. Reena Esmail’s The Light is the Same is featured on Imani’s Grammy-nominated album Bruits. It’s a remarkable amalgamation of Western and Hindustani musical traditions, with a sinewy oboe line (Toyin Spellman-Diaz) introducing the raga on which it is based. A piccolo passage, gently floating above the rest of the ensemble, made for a strikingly ethereal moment, and one was quite taken by the rhythmic complexities of the dance-inflected finale.

The program closed with another piece by Coleman, the Afro-Cuban Concerto, dating from 2001. As the title indicated, the quintet took on a larger than life role, effectively functioning as a mini orchestra. The recurring 6/8 rhythmic gestures were given an energetic workout in the opening “Afro” movement, while the central “Vocalise” proved just as lyrical and songful as the moniker suggested. The closing “Danza” was spirited and played with aplomb, replete with a gleaming horn solo (Kevin Newton) as well as some intricate passagework from the clarinet (Mark Dover).