ProMusica Chamber Orchestra

David Danzmayr, conductor

Vadim Gluzman, violin

Southern Theatre

Columbus, OH

May 11, 2024

Silvestrov: Hymn – 2001

Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

Encore:

Bach: Sarabande from Violin Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004

Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

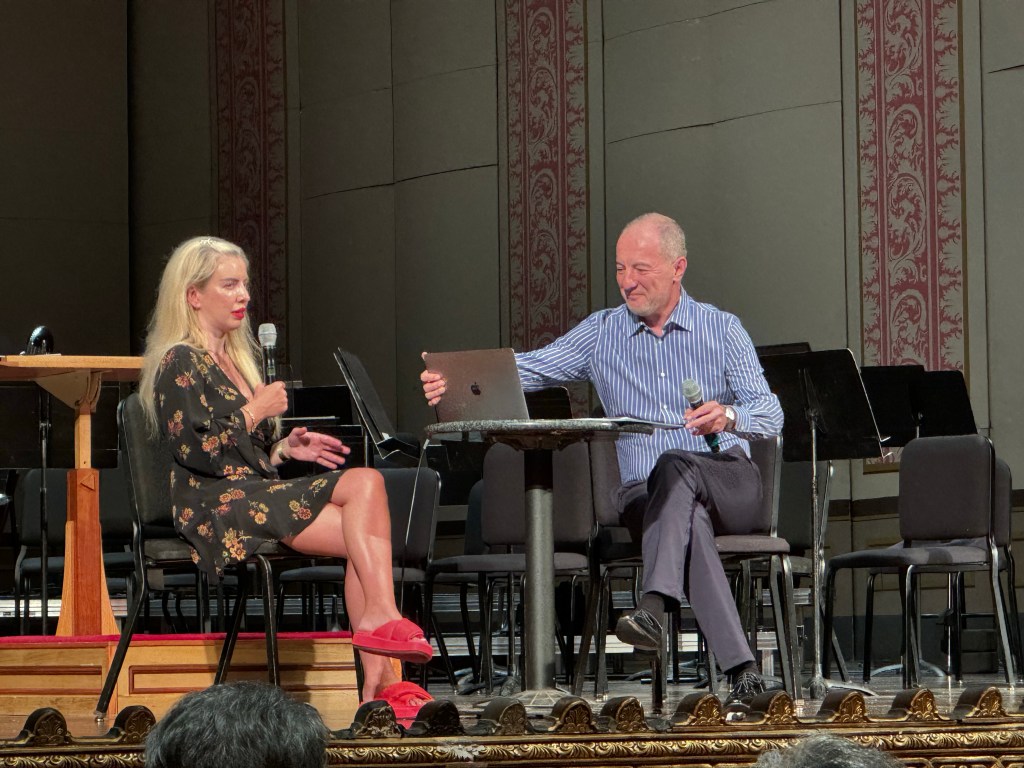

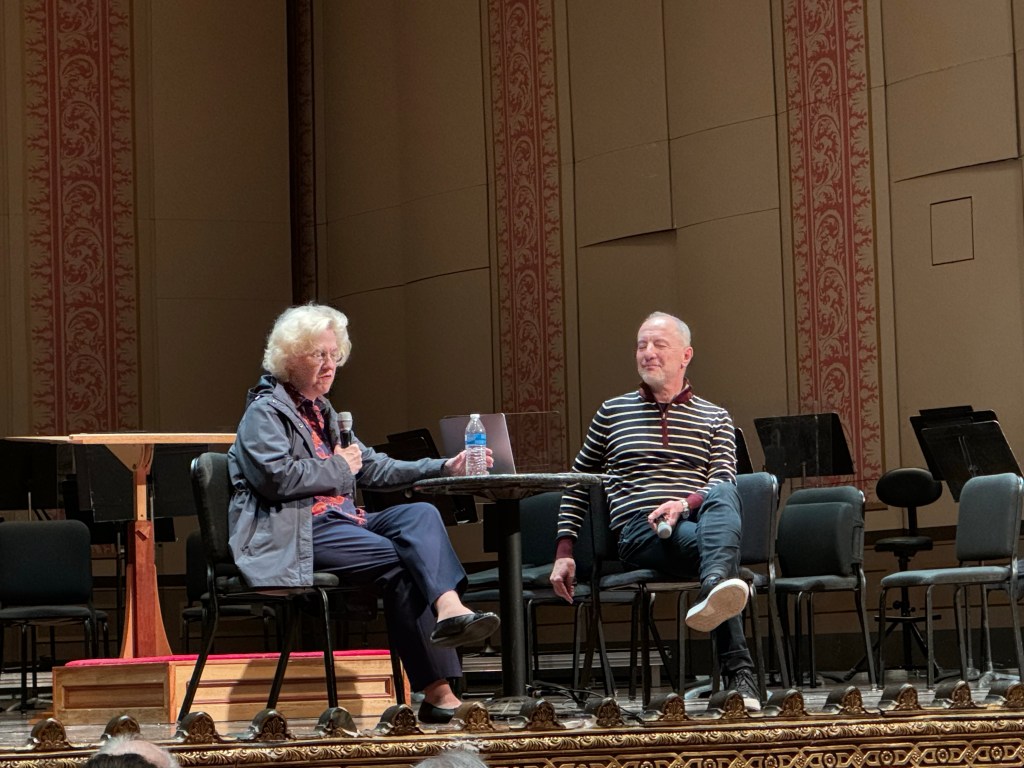

There was a celebratory air to ProMusica’s closing performances of their 45th season in marking a decade of having both David Danzmayr and Vadim Gluzman in the fold as music director and creative partner respectively. As has become tradition, the final weekend was opened with a short performance by students from the Play Us Forward program – this year, an excerpt from Vivaldi’s Autumn – celebrating ProMusica’s impact in the greater Columbus community.

Valentin Silvestrov’s Hymn – 2001 began ProMusica’s program with a lush essay for string orchestra. There were fine solo passages from concertmaster Katherine McLin and principal second violin Jennifer Ross. Meaning was also drawn from punctuated moments of silence, with the Ukrainian composer acknowledging Cage’s 4’33” as an inspiration for this lyrical paean.

Tchaikovsky’s evergreen Violin Concerto served as the evening’s centerpiece, and put on full display the collaborative spark between Danzmayr and Gluzman. It’s a particular pleasure to see Gluzman play this work as he performs on a violin once owned by Leopold Auer, the concerto’s original dedicatee – in other words, the very violin this concerto was written for. I have fond memories of Gluzman performing this work with The Cleveland Orchestra and the late Michail Jurowski a few years ago – a privilege to hear this instrument in this work again.

Matters began with graceful charm, and the violinist filled the Southern with a resonantly lyrical tone. Gluzman gave an impassioned performance, and I was often simply in awe of the sound he drew from his storied instrument (Tchaikovsky must have liked it too!). Fleet fingers pulled off the more rapid passegework, further encouraged by a taut communication with Danzmayr, the product of a fruitful decade.

A choir of winds opened the central slow movement, and Gluzman answered with a long-bowed, somber melody, an articulate dialogue between soloist and orchestra. The finale was of rapid fire excitement, though a downtempo section of distinctly Slavic inflection contrasted before the blistering finish. An enthusiastic ovation brought the violinist back for an encore by Bach, a lovely pendant to the concerto, with Gluzman noting it an apropos choice given Silvestrov’s affinity for Bach.

Last season closed with a Brahms symphony, a feat reprised this past weekend with attention turned to the sunny Second. Once again, ProMusica, buttressed by an expanded string section, proved that the Brahms symphonies can be convincingly performed by a chamber-sized orchestra. A dip in the strings opened, warmly answered by horns and winds, with a particularly rich theme in the cellos to follow. Danzmayr opted out of the long repeat of the exposition, delving right into the energetic development. The slow movement proceeded as a beautifully lyrical paragraph, though seemingly all cares were left behind for the Allegretto grazioso, given with an abandon that was only a warmup for the jubilant finale.